In recent times, the government and players in the telcos have embarked on digitalization projects to reduce the use of cash. Among these is the mobile money and currently, e-currency (e-cedi) project, in which the Central Bank will issue its “own version” of mobile money.

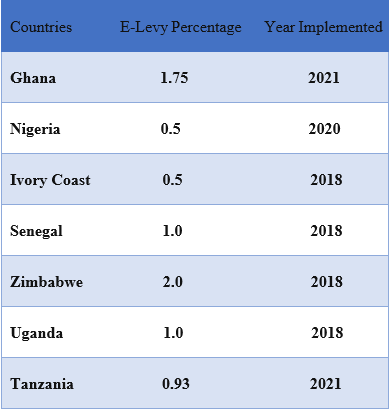

In Africa, several countries have initiated steps to broaden revenue generation in order to strengthen their economies. Thus, widening the tax base on mobile phone-based transactions, airtime, and operators in sub-Saharan Africa has been on the increase in the last decade. Indeed, Rogers and Pedros (2017) find that, in 2015, approximately 26 percent of the taxes and fees paid by the mobile industry in 12 sub-Saharan African countries were related to sector-specific taxation and not from broad-based taxation (i.e., taxes applicable to all sectors of the economy).

Apparently, mobile money taxation in other sub-Saharan countries such as Malawi, DR Congo has been withdrawn. After proposing a 1% tax on mobile money transactions, the Malawi Ministry of Finance officially dropped its plan after facing criticism from mobile network operators (MNO) and consumer rights organizations. The CEO of Telekom Networks Malawi (TNM), the country’s largest MNO, as well as the Consumer Association of Malawi strongly expressed their disdain for the imposition of a tax as a devastating blow to the poorest members of society.

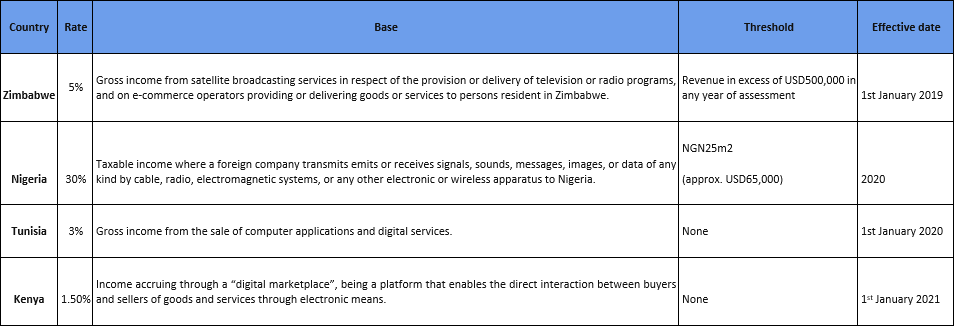

In light of the imminent focus of the African tax authorities on the digital economy hastened along by COVID-19, now is an appropriate time to reflect on the developments of digital services taxes across Africa with a particular focus on direct taxes. Currently, the digital services tax laws have been, or are being, implemented in four African countries that we are aware of, being Kenya, Nigeria, Tunisia, and Zimbabwe.

With the emergence of covid-19 and the imposition of restrictions on movement and the fact that mobile money, bank accounts, and cards have become more closely linked, many people resorted to digital transactions and payment for most of their day-to-day economic activities.

Mobile money has made great strides in increasing access to digital financial services in Ghana and bridging the financial inclusion gap. By November 2021, Ghana had 47.3 million registered users, 18.4 active users and over GHs 80 billion (US$13 billion) value of mobile money transactions performed, according to the UNCDF 2022 report.

The government asserts that the value of digital transactions rose by 120% between February 2020 and February 2021. In the previous year, it rose 44%. The government is aware that most people are now accustomed to online transactions. They are convenient and people will find it difficult to revert to physical transactions, as indicated by the Senyo 2021 report.

The government, as part of strategies to widen the country’s tax net, has announced the introduction of an Electronic Transaction Levy; a 1.75 percent charge on all electronic transactions, including transactions covering mobile money payments, bank transfers, merchant payments, and inward remittance (MoF 2022 Budget Highlights). All these transactions will have the levy imposed on them, which will be borne by the sender.

This levy will however be waived for Momo transactions that amount to GH¢100 or less in a day or approximately GH¢3,000 per month. This fee, according to the Finance Minister, Ken Ofori-Atta, is to enhance financial inclusion and protect the vulnerable.

The government says portions of revenue collected from the levy will be used to support entrepreneurship, youth employment, cybersecurity, digital, and road infrastructure among others, but a majority of Ghanaians have every reason not to believe this claim.

This 1.75 percent charge on all electronic transactions has been widely criticized on the grounds that it will disadvantage the poor. However, Charles Adu Boahen, the Minister of State at the Finance Ministry, does not side with these suggestions, stating on the Citi Breakfast Show that the exemptions given to MoMo transactions below GH¢100 are rather in the interest of poor Ghanaians.

The total value of MoMo transactions for 2020 was estimated to be over GHS 500 billion, as compared to GH¢78 billion in 2016. Total mobile money subscribers and active mobile money users have grown by an average rate of 18% and 16% between 2016 and 2019 respectively. The government, therefore, believes there is a potential to increase tax revenues by bringing into the tax bracket transactions undertaken in the “informal economy”.

As many people, including those in the informal sector, use mobile money, the government sees it as an easy way of taxing the informal sector. Estimates show that in 2020, the total volume of mobile money transactions was over $99 billion (GH¢561 billion) far surpassing check and cash transactions which stood at $29 billion.

Given the potential revenue the government can generate, and the fact that they’re unable to generate an innovative solution to tax the informal sector, mobile money taxation appears to be the easy way out. However, the initial response to the announcement of this levy has been one of displeasure and fears that it will affect the country’s current digitization agenda.

Were there any Stakeholder consultations prior to this levy?

Best practices suggest that vulnerable groups should be put at the center of such policymaking to leave no one behind in the digital era; broad consultations and public-private dialogue are needed to inform the action; weighted waivers could be considered to provide solutions that take into account user-profiles and transaction types.

CSOs and Advocacy think-tanks, including the Minority group in Parliament, taunted that there weren’t broad consultations before the pronouncement of the e-levy bill. Thus, they are championing that there must be ample time to receive memoranda on the levy and undertake broad stakeholder consultation before its consideration.

The government expectation was that if the budget appropriation is passed by Parliament on the 21st December 2021, the implementation of the new policy will come into force effective February 1, 2022. However, the tension between lawmakers over the proposed levy on electronic transactions led to a brawl on the floor of parliament which led to the postponement of the approval of the bill.

Based on parliamentary bye-laws, a vote will have to be held (based on headcount and/or division) to finalize the bill’s approval, but outcomes remain unclear in a tense political atmosphere. Meanwhile, sentiments on the streets are negative towards the e-levy. The Mobile Money Agents’ Association of Ghana, whose members operate shops that enable mobile money transactions, planned December last year, to express their displeasure by starting a strike, as they forecast the levy as very regressive and critical to the survival of their businesses.

Similarly, Fintech experts posit that given the direct and indirect benefits Fintech contributes to economies, this e-levy will become an additional problem for already struggling Fintech startups. It appears that the government is only thinking of short-term revenue gains. Thus, the government should relook at the implementation and strategically target the tax instead of the blanket e-levy on digital payment. It should be guided by lessons from other countries like Uganda that have also implemented mobile money tax.

Resources:

#GhBudget: 1.75% levy slapped on MoMo, other electronic transactions

https://www.pulse.com.gh/entertainment/celebrities/175-momo-tax-is-high-we-cant-pay-nana-aba-anamoah-to-akufo-addo/bhbzn5j

₵100 limit for e-levy on mobile money transactions is to protect the poor – Deputy Finance Minister

Ghana slaps 1.75 Percent E-levy on MoMo, electronic transactions

https://www.ghanaweb.com/GhanaHomePage/business/Government-places-1-75-tax-on-e-transactions-including-MoMo-bank-transfers-1403875

https://qz.com/africa/2092221/ghana-introduces-a-1-75-percent-levy-on-electronic-transactions/amp/

https://qz.com/africa/2104810/ghanas-lawmakers-got-into-a-fight-over-1-75-percent-e-levy/amp/

https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/ke/Documents/tax/What%20are%20the%20key%20lessons%20on%20taxation%20of%20the%20digital%20marketplace.pdf